num_1 = 1.510 Basics

10.1 Objects

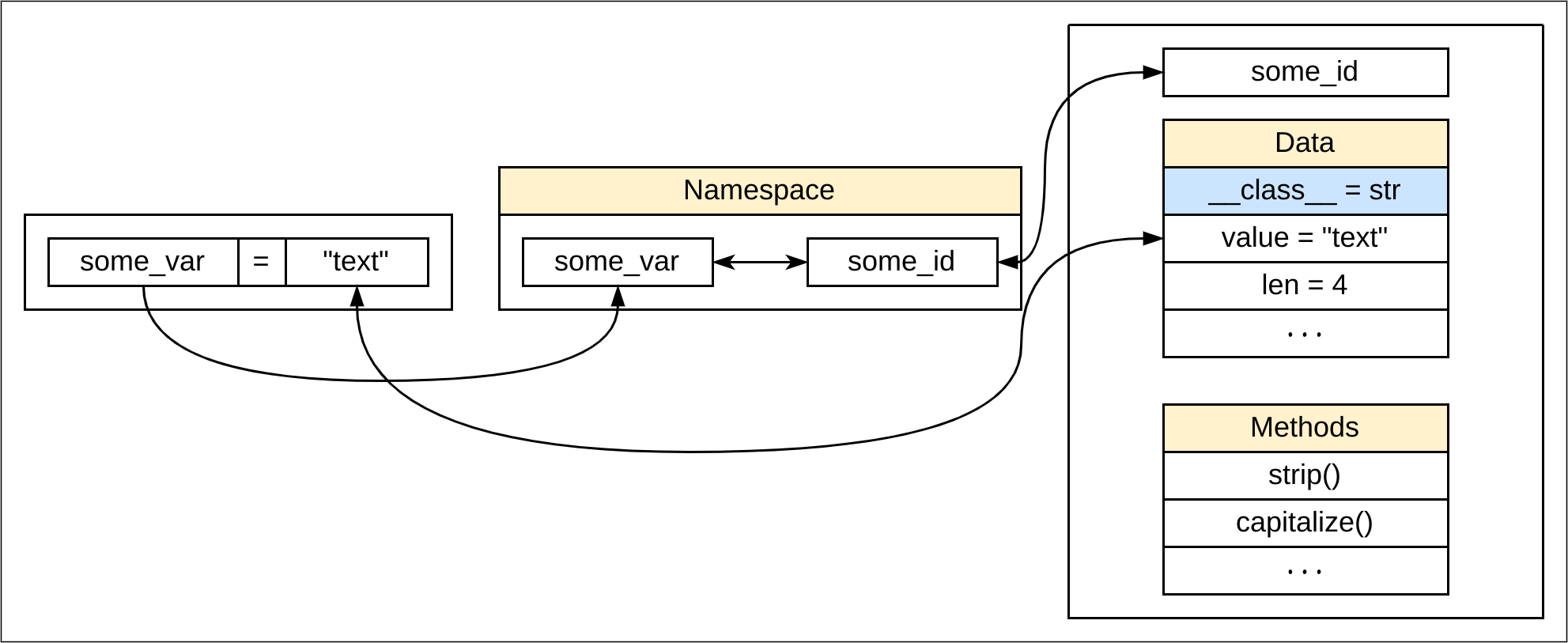

In Python everything is an object stored on RAM (random access memory), and is looked up using object reference that is a memory address on RAM.

Objects are fundamental to object oriented programming, which will be covered in the OOP section.

Object stores information in attributes which are of 2 fundamental forms.

- data attributes

- operations

To understand the idea think of an object as object = data + operation where,

- data = noun and operation = verb

- data = state and operation = behavior

For example, consider an integer “text” stored as an object in Python. It has data type attributes like value which is the “text” and numerous operations like capitalize which returns another string “Text”. The actual implementation has more details, this is simplification of the general concept.

Data attributes are responsible for storing the information that defines the state of an object.

Every object has special data attribute which defines what type of object it is. In Python it is __class__.

Operations are other type of attribute, which provide functionality. They are functions with some additional features and are often referred to as methods.

10.1.1 dot operator

Dot operator .gives access to object’s attributes, data and operations.

num_1.as_integer_ratio()>>> (3, 2)10.2 Variables

10.2.1 Introduction to variables

Variables are named references that provide a handle to the object. They are stored separately on RAM in a separate table called namespace.

Namespaces are mapping between variable names and reference to objects which can be used to lookup memory address of the object.

Note that memory address is not constant, the language interpreter stores created objects at available memory address and deletes them when not needed. On many occasions the memory address will change, e.g. re running a program. That is where variables and namespaces come in.

Variables provide handle to objects for

- reuse and passing around objects

- performing operations

In Python, variable are defined using the = operator.

When a variable is defined for example

some_var = "some text"- a string type object

"some text"is created in RAM which hassome_id some_varvariable name is bound to"some text"object created- this is referred to as name binding

- variable name

some_varand memory address of object"some text"are stored in a namespace

Below figure illustrates the relationship between a variable name and object.

Once the language interpreter sees what type of object it is, it knows what is the structure of data and operations stored in the object. Hence, the associated variable name has access to the attributes.

10.2.2 Deciding variable names

10.2.2.1 Must-follow

- case sensitive

- start with

_orletter(a-z A-Z) - followed by any number of

_, letters or digits - cannot be one of reserved words

Below code can be used to check keyword list in Python.

import keyword

print(keyword.kwlist)|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10.2.2.2 Should-follow

_my_var: names starting with single underscore- used for

privateorinternalobjects - not exported by

from module import *

- used for

avoid using names with dunder

__my_var: names starting with double underscore- used to mangle class attributes in class chains

__my_var__: names starting and ending in double underscore- system defined names used in class internal attributes

10.2.2.3 PEP-8 Conventions

PEP refers to Python enhancement proposals which have detailed documentation about the rationale and description of changes to Python language specifications.

PEP-8 is related to Python code styles and is highly recommended read. Below are the conventions suggested for variable names. These will be used all through the course with few exceptions.

Following these conventions makes the code readability and understanding the code easy for both the writer and users.

| Object Type | Convention | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Packages |

|

utilities |

| Modules |

|

db_utils.py or dbutils.py |

| Classes | upper CamelCase | BankAccount |

| Class instances | lower snake_case | bank_account |

| Functions | lower snake_case | my_func |

| Variables | lower snake_case | my_var |

| Constants | upper SNAKE_CASE | MY_CONST |

| Dummy variables | underscore | _ |

10.2.3 Python features

10.2.3.1 Dynamic type

In Python, variable type do not need to be declared and same variable can be bound to different type of objects.

This is leads to terms like Python is a dynamically typed language.

Opposite to dynamic type is strict type, e.g. C, where once a variable is declared to point to string objects it can only store string objects.

some_var = 10

some_var = "some text string"print(f'{some_var=}')>>> some_var='some text string'Variable type can be declared for assistance and code readability, but does not enforce the type, which means it can be bound to other object type.

It is not recommended to declare type and then use different type of object.

PEP-487 has more detailed discussion around this.

some_var:str = "some text string"

some_var:int = 10print(f'{some_var=}')>>> some_var=1010.2.3.2 Multiple assignment

To exchange values of a set of variables you do not need temporary assignments. Below examples illustrates this.

a = 10; b = "some text"; c = ["this", "is", "a", "list"]print(f'{a=}, {b=}, {c=}')>>> a=10, b='some text', c=['this', 'is', 'a', 'list']a, b, c = c, a, bprint(f'{a=}, {b=}, {c=}')>>> a=['this', 'is', 'a', 'list'], b=10, c='some text'10.3 Commonly used syntax

10.3.2 Newline

- New lines can be introduced in multiple ways

- explicit method

- break lines using

\ - join lines using

;

- break lines using

- implicit method: Expressions within

(),[],{}- can be broken into multiple lines

- can contain comments

- can have trailing commas

- explicit method

- New line syntax can be used to enhance code readability

10.3.2.1 Explicit method example

some_var_1 = 10

some_var_2 = 20

some_var_3 = 30

some_var_4 = 40

if some_var_1 > 5 and some_var_2 > 10 and some_var_3 > 20 and some_var_4 > 30:

print('yes')When the code becomes too long to fit or is too short it is useful to use explicit method to join or break lines to improve code organization and readability.

some_var_1 = 10; some_var_2 = 20

some_var_3 = 30; some_var_4 = 40

if some_var_1 > 5 and some_var_2 > 10 \

and some_var_3 > 20 and some_var_4 > 30:

print('yes')10.3.2.2 Implicit method example

Expressions in (), [] or {} can be split into multiple lines without needing explicit use of backslash (\). Optionally they can contain comments.

Note that trailing commas are allowed, illustrated in second example.

a = (

"item 1",

"item 2",

"item 3"

)a = [

1, # first item

2, # second item

3, # third item

]10.3.3 Blocks (indentation)

Python uses indentation to isolate distinct blocks, like control flow blocks (if, while), functions (def), classes (class). This improves code readability.

Indentation can be made using special tab characters or spaces. It is recommended to use 4 spaces and is generally a good choice. Below is an example, to illustrate how indentation improves code readability.

import math

def calc_circle_area(r=1, pi=math.pi):

if r < 0:

print("radius should be >= 0")

else:

return pi*(r**2)Editors allow you to choose the method and amount of indentation to use. So in VSCode it is recommended to set it to 4 spaces. “Editor: Tab Size” is the relevant setting which is documented at link.

10.4 Functions

This section provides introduction to some basic functions which will be used to explain some underlying concepts in topics that follow.

Focus on

- understanding at a high level what the function does

- getting used to executing small pieces of code (in jupyter notebooks)

- using variable assignment

Ignore the details of f'' string formats for now, they are there for formatting output. They will be covered later in data types section under string operations.

10.4.1 type

type(_obj): returns object type

var_1 = 10

var_2 = 10.0

var_3 = "string"type(var_1), type(var_2), type(var_3), type(10.2)>>> (<class 'int'>, <class 'float'>, <class 'str'>, <class 'float'>)10.4.2 id

id(_obj): returns object memory reference idhex(_integer)converts to hexadecimal for better readability

_string_1 = "some text"id(_string_1), hex(id(_string_1))>>> (124205596871664, '0x70f6de7b0bf0')10.4.3 is

a is b: check if a and b refer to same object

This means checking if the memory address of the given variables or objects is same.

In the example below a list object [10] is created and both a and b are bound to the same object. Therefore a is b returns true.

a = b = [10]print(f'{a is b = }\n{hex(id(a))=}\n{hex(id(b))=}')>>> a is b = True

>>> hex(id(a))='0x70f6ea1d3e80'

>>> hex(id(b))='0x70f6ea1d3e80'In the example below a list object [10] is created and variable a is bound to that object. Then variable b is bound to the object that a is bound to.

a = [10]

b = aprint(f'{a is b = }\n{hex(id(a))=}\n{hex(id(b))=}')>>> a is b = True

>>> hex(id(a))='0x70f6de787540'

>>> hex(id(b))='0x70f6de787540'Since [10] is a list type object, even though c and d assignments look the same, they point to different objects.

c = [10]

d = [10]print(f'{c is d = }\n{hex(id(c))=}\n{hex(id(d))=}')>>> c is d = False

>>> hex(id(c))='0x70f6ea1d3e80'

>>> hex(id(d))='0x70f6de7b48c0'Above examples illustrate subtle points about variable and object bindings which lead to a lot of implications while using mutable and immutable objects. This is covered in more detail in next section on data types and rest of the book.

10.5 Modules and import

Modules in Python refer to different things, based on context.

- a file with

.pyextension containing Python code - an object once a

.pyfile or package is imported usingimportstatement

Packages are special type of modules, a folder containing Python files.

One of the important use-case of these specifications is to use external code. Python standard library has a lot of built in functionality for various use cases. The modules and packages contained in the standard library can be imported and used as required.

Import system in Python provides ways of managing objects in code and files. This is introduced here for basic usage in examples. All this is covered in detail in Architecture part.

In the example below,

mathmodule is imported usingimportstatement- objects: definitions are accessed using dot operator

import math

print(math.pi)>>> 3.141592653589793print(math.ceil(10.2))>>> 1110.6 Executing Python files

There are 2 main ways to execute a Python (.py) file using command line.

<path to python executable> <path to file>- can take relative path

- for a regular package

- only

__main__.pyis executed if package name is used __main__.pyor__init__.pycan be given explicitly

- only

<path to python executable> -m <file name without extension>- cannot take relative paths

- command has to be executed from the directory containing the file

- if the file is in a directory below the shell directory then dot notation can be used

- e.g.

python3 -m sub_dir.file_1

- e.g.

- in case of a regular package,

__init.pyand__main__.pyboth are executed

Since using the first approach, a Python file can be executed from any directory it is the preferred approach.

10.6.1 Executing one script from another

The recommended approach for executing one script from another is to keep the files in same folder and then use import.

For example, file_1.py has to execute file_2.py. Place file_2.py in same folder as file_1 then use import file_2 in file_1.py. Whenever file_1.py is executed it will execute file_2.py.

10.3.1 Comments (

#)Comments are text within code which is not evaluated and is used for documentation and code readability.

There are 2 basic rules related to comments.

python ignores and does not parse/evaluate the line content after

#cannot use

#just after assignment operator=10.3.1.1 Examples

10.3.1.1.1 Example 1

Below is simple usage to document the code.

10.3.1.1.2 Example 2

In the example below, variable

num_in_commentgives an error while trying to print on line 2 because line 1 is commented and not evaluated, therefore there is no variablenum_in_commentin namespace.10.3.1.1.3 Example 3

Below example illustrates incorrect usage of

#after=.