print("condition True") if 1 > 0 else print("condition False")>>> condition TrueControl the flow of a computer program

When do you need to control the flow of a program?

if...[elif]....[else], match...casefor...[else], while...[else] blockstry...[except]...[else]...[finally] blocksNote: square brackets are generally used to represent something optional

As a beginner to programming conditional blocks and loops are sufficient to get started.

Error handlers are not needed for most of the basic stuff, but there are a few cases where it is useful to know the basics. For example it is useful to know the basics of using try block for a few situations. Most of debugging is based on the concepts related to error handlers. Editors provide support for debugging using these concepts. Developers rely heavily on using these concepts to handle expected errors differently. Therefore it is useful to understand the basics of error handling as it is certain to make errors and handle them.

Asynchronous input/output (asyncio) and parallel computing are advanced topics used to increase efficiency of larger programs. They are not covered.

For all of the control flow techniques, conditionals, loops and error handlers

Conditional blocks use conditions to control and change the flow of a program. Conditions are created using boolean operations.

if...[elif]...[elif]...[else] blocks

match...case...[case_] blocks

if blockif blocksif blocks are used to execute some code only when a condition is evaluated to True.

Below are possible forms of if block.

if condition:

# if block contentif condition:

# if block content

else:

# else block contentif condition_1:

# if block content

elif condition_2:

# elif block 1 content

elif condition_3:

# elif block 2 content

else:

# else block content# execute some short expression conditionally

if condition: <short expression>if block

if statement with an expression ending in colon (:)if block

elif (else if) blockselse blockelif and else is same as ifPython additionally provides a ternary form for short, one line conditionals. Below is the syntax, where X and Y are short expressions to be evaluated and returned.

Ternary operator is useful for code readability. It removes the requirement for a multiline if block for quick checks required in code.

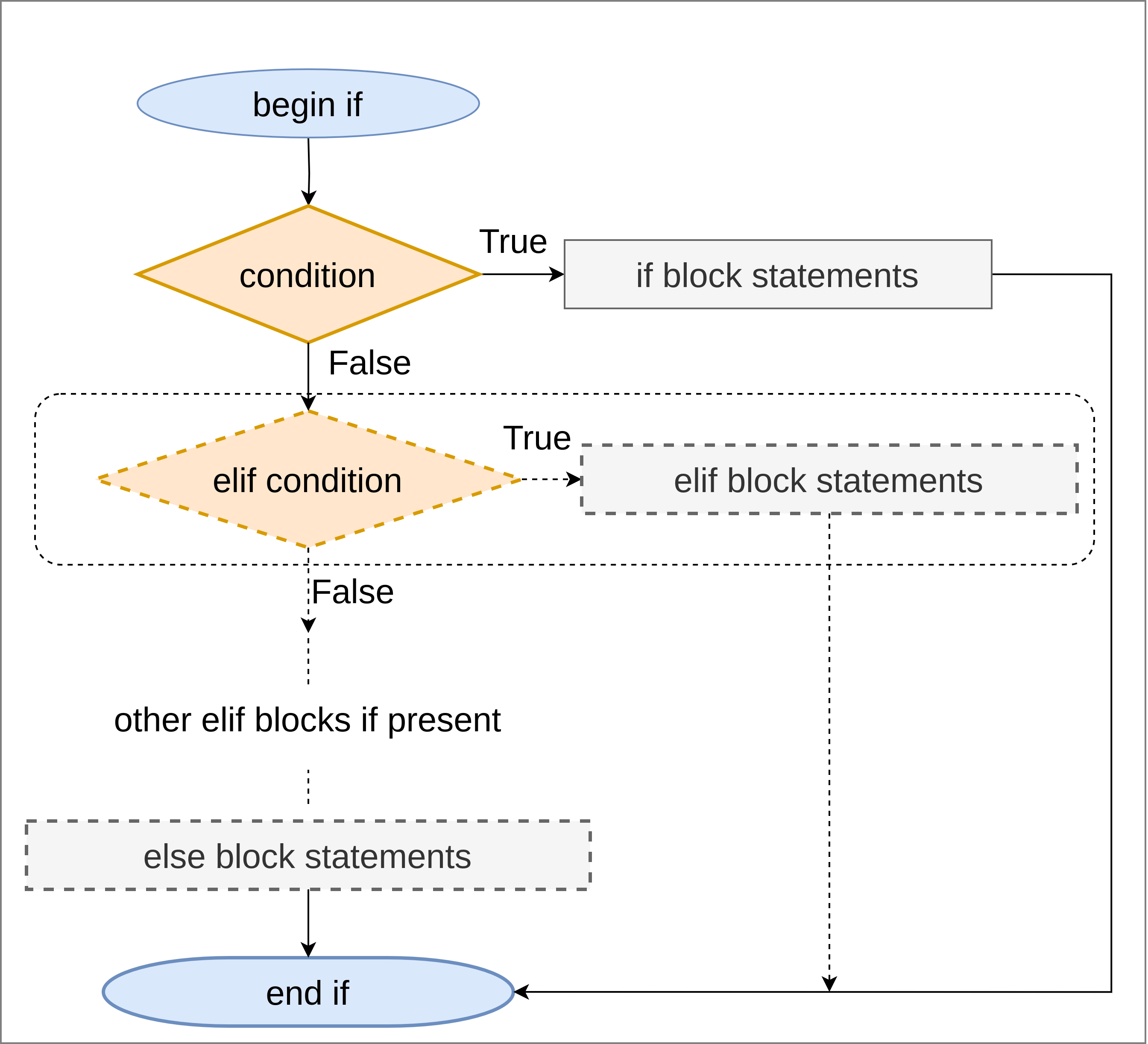

X if condition else Yprint("condition True") if 1 > 0 else print("condition False")>>> condition Trueprint("condition True") if 1 == 0 else print("condition False")>>> condition FalseFlow diagram below illustrates the control flow for a if block.

Basic idea

if and elif conditions sequentially

True

False

else block if present and exitsome_num = 12

if some_num >= 0:

print(f'{some_num} is positive')>>> 12 is positiveelse blocksome_num = 12

if some_num >= 0:

print(f'{some_num} is positive')

else:

print(f'{some_num} is negative')>>> 12 is positiveelif blocksome_num = 12

if some_num == 0:

print(f'{some_num} is zero')

elif some_num > 0:

print(f'{some_num} is positive')

elif some_num < 0:

print(f'{some_num} is negative')>>> 12 is positiveelif and elsesome_num = 12

if some_num == 0:

print(f'{some_num} is zero')

elif some_num > 0:

print(f'{some_num} is positive')

else:

print(f'{some_num} is negative')>>> 12 is positivematch...case blockMatch blocks are used if some object is to be tested against multiple cases. It can be achieved using if blocks but match blocks are better for code readability and ease of use for the given use case.

_ is optional and for case when none of the options match.

match some_obj:

case option_1:

# do something and exit

case option_2:

# do something and exit

[case _:

# do something and exit

]

if some_obj == option_1:

# do something and exit

elif some_obj == option_2:

# do something and exit

[else

# do something and exit

]More information can be found at Python documentation for match statements.

for blockwhile blockIterating is a common term which refers to going through elements of a collection. Iterables and iterators in Python are based on this idea.

for blockfor item in iterable:

# do something

# item is available

print(item)

for i in range(n):

# do something

# i is available

print(item)

for item in iterable: print(item)Fundamental form

for keyword declares the start of a for blockitem in iterable is the generic form:, colon, to declare end of for declarationUsing this fundamental form other variation are created. e.g.

range(n) function is used to loop through fixed number of times

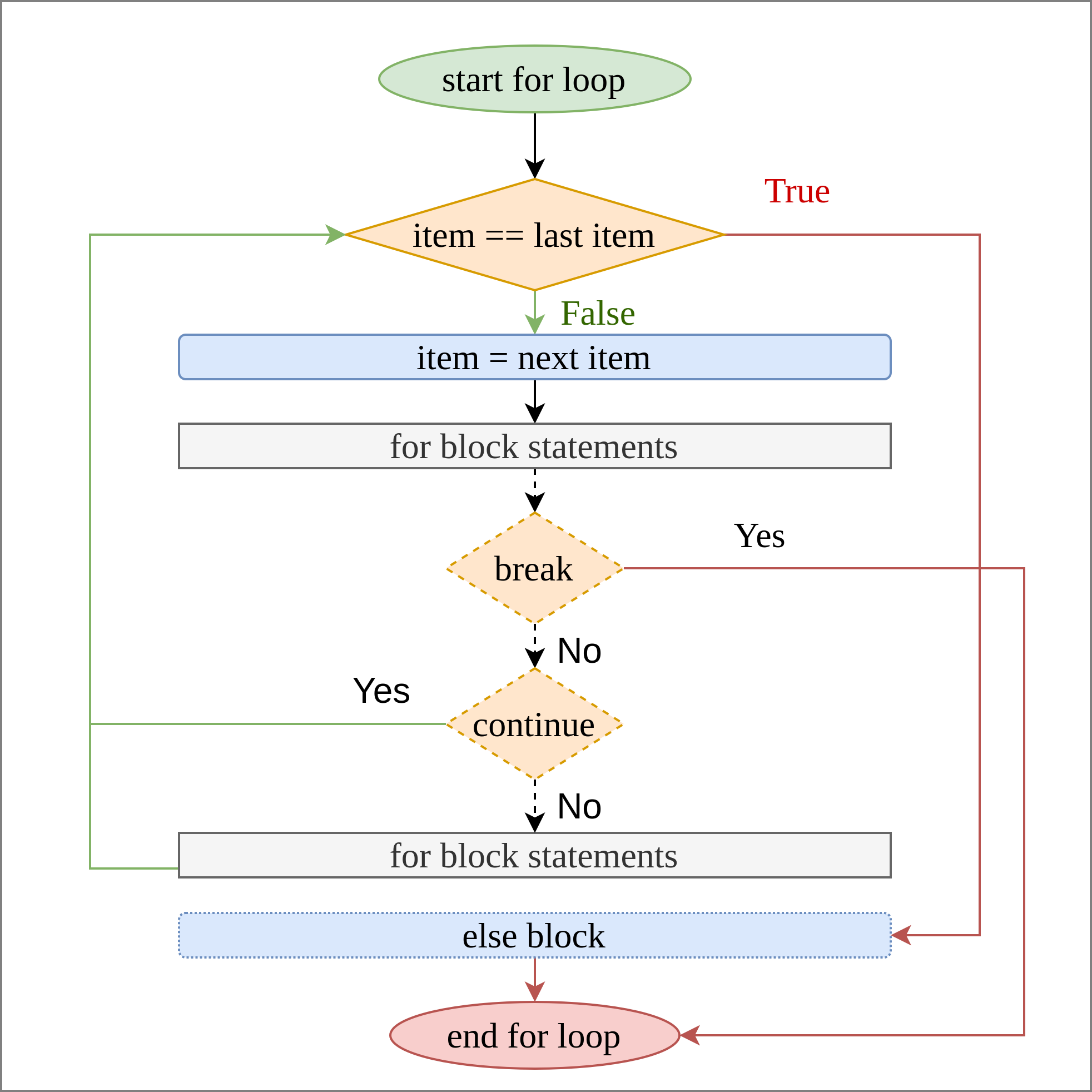

for i in range(10): i takes values 0 through 9for i in range(1, 11): i takes values 1 through 10range() function is discussed at Section 11.7continuecontinue clause causes the loop to jump to next iteration without executing remaining lines in loop.

In the below structure, when the condition is true, item will not be printed.

for item in iterable:

# do something

# item is available

if condition:

continue

print(item)Continue is useful if you need to skip execution of some code for certain elements of the iterable.

break and elsebreak clause causes exit of the innermost loop

else clause

break is hitfor item in iterable:

# do something

# item is available

if condition:

break

print(item)

else:

print("No break found")

n_max = 20

evensoddsn_max = 20

evens = []; odds = []

for i in range(1, n_max + 1):

evens.append(i) if i % 2 == 0 else odds.append(i)print(evens)>>> [2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20]print(odds)>>> [1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19]continueIn the below example only odd numbers are printed as the loop hits continue for even numbers.

for i in range(5):

if i % 2 == 0: continue

print(i)>>> 1

>>> 3break and elsecorrect_list = [65, 24, 53, 91, 59, 81, 93, 7, 78, 10]

for num in correct_list:

if num < 0 or num > 100:

print(f"validation failed, list contains {num}")

break

else:

print("validation successful")>>> validation successfulincorrect_list = [97, 144, 115, 127, 33, 99, 85, 109, 21, 110]

for num in incorrect_list:

if 0 <= num <= 100:

continue

else:

print(f"validation failed, list contains {num}")

break

else:

print("validation successful")>>> validation failed, list contains 144Notice that

elseblock is useful in this situation as it is run only when for loop iteration is complete without hittingbreakstatement.

There are different ways to structure the same conditions and required outcome.

Print table of numbers from 1 through 12 for multiplication with 1 through 10.

for i in range(1, 13):

for j in range(1, 11):

end = "\n" if j == 10 else "\t"

print(i*j, end=end)>>> 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

>>> 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

>>> 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 27 30

>>> 4 8 12 16 20 24 28 32 36 40

>>> 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50

>>> 6 12 18 24 30 36 42 48 54 60

>>> 7 14 21 28 35 42 49 56 63 70

>>> 8 16 24 32 40 48 56 64 72 80

>>> 9 18 27 36 45 54 63 72 81 90

>>> 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

>>> 11 22 33 44 55 66 77 88 99 110

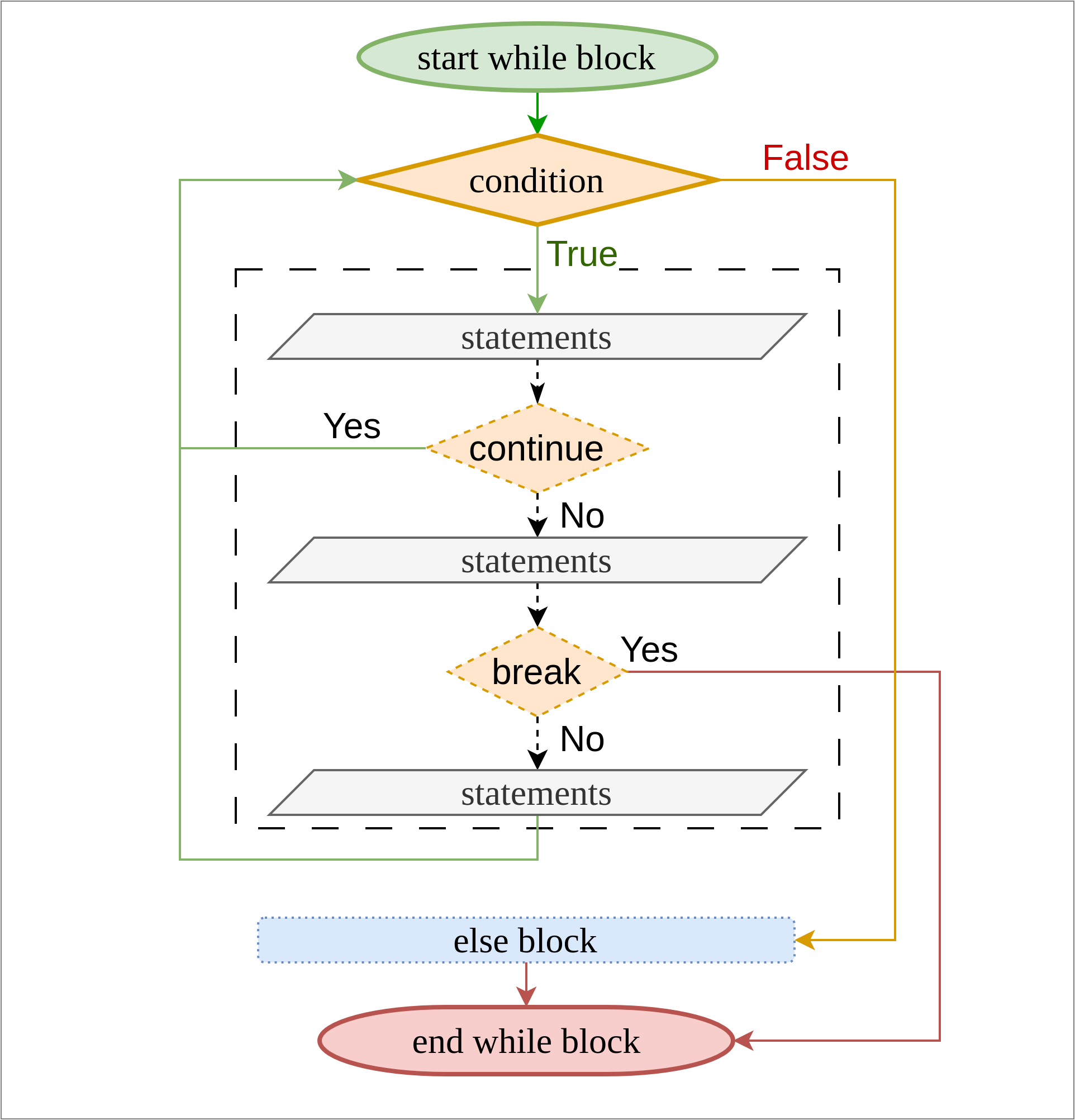

>>> 12 24 36 48 60 72 84 96 108 120whilewhile condition:

# code block

[continue]

# code block

[break]

[else]:

# code blockTrue or break statement is hitcontinue, break, else clauses are optionalBelow diagram illustrates the control flow for a while loop.

while block contents are executed repeatedly until condition is True

continue statement is hit

break statement is hit anywhere loop exits

else block even if presentFalse

else block is executed if present

A while loop is needed when number of repetitions is not known in advance

ctrl + c to bail outcondition = True

while condition:

# forget to set condition = False

print("inside infinite loop")a = 6

while a != 0:

a -= 1

if a == 2:

print(f'break block: {a = }')

break

if a == 3:

print(f'continue block: {a = }')

continue

print(f'main block: {a = }')>>> main block: a = 5

>>> main block: a = 4

>>> continue block: a = 3

>>> break block: a = 2Below is gcd algorithm to find the greatest common divisor of 2 integers using while loop.

% gives the remainder)Since the number of repetitions needed are based on input, while loop is suitable for this.

a, b = 9, 6

rem = a % b

while rem != 0:

print(f'{a = }, {b = }, {rem = }')

a, b = b, rem

rem = a % b

print(f'{a = }, {b = }, {rem = }')

print(b)>>> a = 9, b = 6, rem = 3

>>> a = 6, b = 3, rem = 0

>>> 3Iterator is an object that can be iterated upon its elements only once. It is exhaustible.

Iterable is an object that can be iterated upon its elements repeatedly.

Both cannot be viewed directly and have to be converted into a list or tuple to view contents.

some_tuple = "a", "b", "c", "d"

some_iterator = enumerate(some_tuple)print(list(some_iterator))>>> [(0, 'a'), (1, 'b'), (2, 'c'), (3, 'd')]print(list(some_iterator))>>> []| Iterators | Iterables |

|---|---|

zip |

range |

enumerate |

dictionary.keys |

open |

dictionary.values |

dictionary.items |

It is very common situation where both index and value is needed while iterating over a sequence (sequence is also an iterable).

Python provides a special function, enumerate(iterable) to access index and value of items in an iterable.

some_tuple = "a", "b", "c", "d"

list(enumerate(some_tuple))>>> [(0, 'a'), (1, 'b'), (2, 'c'), (3, 'd')]for idx, item in enumerate(some_tuple):

print(f'{idx=}, {item=}')>>> idx=0, item='a'

>>> idx=1, item='b'

>>> idx=2, item='c'

>>> idx=3, item='d'It is possible to have access to index without enumerate function, which is lengthier, inconvenient and less efficient, hence not required while using Python.

for idx in range(len(some_tuple)):

print(f'{idx=}, item={some_tuple[idx]}')>>> idx=0, item=a

>>> idx=1, item=b

>>> idx=2, item=c

>>> idx=3, item=dPython provides a zip(iterable1, iterable2, ...) function which returns an iterator with tuples of elements of iterables provided until the shortest iterable is exhausted.

This is helpful when multiple iterables are needed to be iterated through in some connected way.

some_list = [1, 2, 3]

some_tuple = (4, 5, 6)

list(zip(some_list, some_tuple))>>> [(1, 4), (2, 5), (3, 6)]result = []

for e1, e2 in zip(some_list, some_tuple):

result.append(e1 + e2)

print(result)>>> [5, 7, 9]This can be achieved without zip but again since it is lengthier and inconvenient, it is not recommended while using Python.

result = []

for idx in range(len(some_list)):

result.append(some_tuple[idx] + some_list[idx])

print(result)>>> [5, 7, 9]Python provides multiple functions to help iterating over dictionaries.

d.keys()d.values()d.items()All of these return a view object which is an iterator. Most commonly used is d.items() as it provides access to both key and value.

some_dict = {"key 1": "value 1", "key 2": "value 2", "key 3": "value 3"}

for k, v in some_dict.items():

print(f'key = {k}, value = {v}')>>> key = key 1, value = value 1

>>> key = key 2, value = value 2

>>> key = key 3, value = value 3It is important to remember that while iterating through mutable collections (list, dict, set) it is recommended not to modify the collection as it gets complicated to handle unexpected situations. So best to use the solutions provided when in doubt rather than introducing a bug.

If the collection is immutable then modifying is not allowed and generally not used.

Another thing to note is modifying the collection in this context refers to changing the structure of collection, e.g. deleting an item. It does not refer to modifying the value of an item within the collection.

Solutions to this are, if a mutable collection is to be modified then

Below are some examples to illustrate when things go wrong when modifying a mutable collection while iterating through it.

In the list in example all numbers <= 3 were to be removed, but there is bug due to modifying the list while iterating over it.

Note that 2 is not removed. Figuring out in this case is simple. In the 2nd iteration 1 was already removed from the list and second item was 3 not 2.

This is a simple example hence finding the bug is easy, but as programs get larger it becomes difficult and inefficient to find such bugs.

nums = list(range(1, 6))

print(nums)>>> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]for num in nums:

if num <= 3:

nums.remove(num)

print(nums)>>> [2, 4, 5]In case of dictionary it gives a run time error.

some_dict = {"k1": "v1", "k2": "v2", "k3": "v3"}

for k, v in some_dict.items():

if k == "k2":

del some_dict[k]>>> Error: RuntimeError: dictionary changed size during iterationList

nums = list(range(1, 6))

new_nums = []

for num in nums:

if not num <= 3:

new_nums.append(num)print(nums)>>> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]print(new_nums)>>> [4, 5]Dictionary

some_dict = {"k1": "v1", "k2": "v2", "k3": "v3"}

new_dict = {}

for k, v in some_dict.items():

if not k == "k2":

new_dict[k] = vprint(some_dict)>>> {'k1': 'v1', 'k2': 'v2', 'k3': 'v3'}print(new_dict)>>> {'k1': 'v1', 'k3': 'v3'}List

nums = list(range(1, 6))

print(nums)>>> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]for num in nums.copy():

if num <= 3:

nums.remove(num)print(nums)>>> [4, 5]Dictionary

some_dict = {"k1": "v1", "k2": "v2", "k3": "v3"}

print(some_dict)>>> {'k1': 'v1', 'k2': 'v2', 'k3': 'v3'}for k, v in some_dict.copy().items():

if k == "k2":

del some_dict[k]print(some_dict)>>> {'k1': 'v1', 'k3': 'v3'}given the number of rules and syntax there are a lot of opportunities for errors

2 broad categories

Syntax error

a =, 2>>> invalid syntax (<string>, line 1)# try:

# 1/0

# except Exception as e:

# print(e)

eg_num = 1/0>>> Error: ZeroDivisionError: division by zeroWhen a run time error occurs, program stops and exception messages are printed along with the traceback. Traceback is a track of where the error occurred in the program to which part of the program lead to running of the line which caused the error.

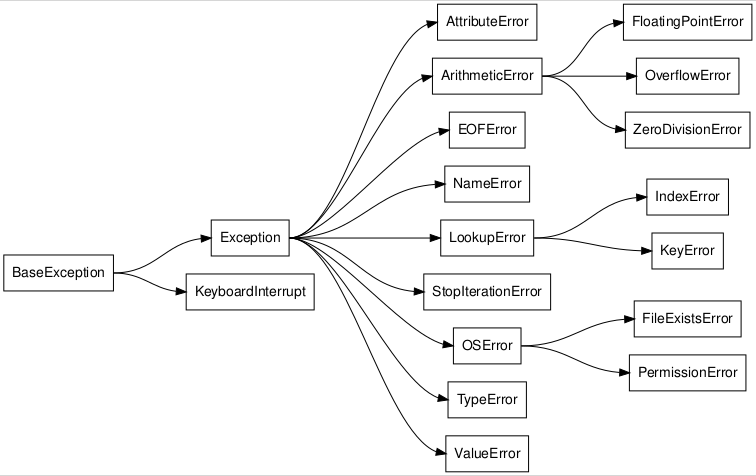

Python has some built-in known exceptions or error types. Exceptions are objects built using object oriented programming.

Exception: base catch almost all errorsZeroDivisionError: division by zeroTypeError: operation not supported by type[s] used in operationException type object is created which has information regarding

Exception typeBelow figure shows Python’s built-in Exception hierarchy. More details can be found at Python documentation for built in exceptions.

raiseraise statements causes the program to stop with default exception. Optionally a known error can be passed with a custom message, e.g. raise ValueError("Invalid input"). raise statement can be used anywhere in the program but is suited for use with try and while blocks, when an expected error is intercepted and has to handled differently.

raise ValueError("some custom message")Below are some examples of common errors which are recommended to be tried and experimented in jupyter notebook cells. See the error messages and map them to the Exception hierarchy. Look at the traceback to see how it is structured.

1/0>>> Error: ZeroDivisionError: division by zeroundefined_var_name>>> Error: NameError: name 'undefined_var_name' is not definedsome_list = [1, 2, 3]

print(some_list[10])>>> Error: IndexError: list index out of rangefloat("text")>>> Error: ValueError: could not convert string to float: 'text'"abc"*"xyz">>> Error: TypeError: can't multiply sequence by non-int of type 'str'try blockstry...except blocks are used to intercept and handle expected run time errors differently. It provides many options like

Note that exception handling has a large number of specifications which can be combined in a lot of ways which can lead to complexity in the beginning. This is being covered with the objective of simple usage. All the specifications are for completeness and information.

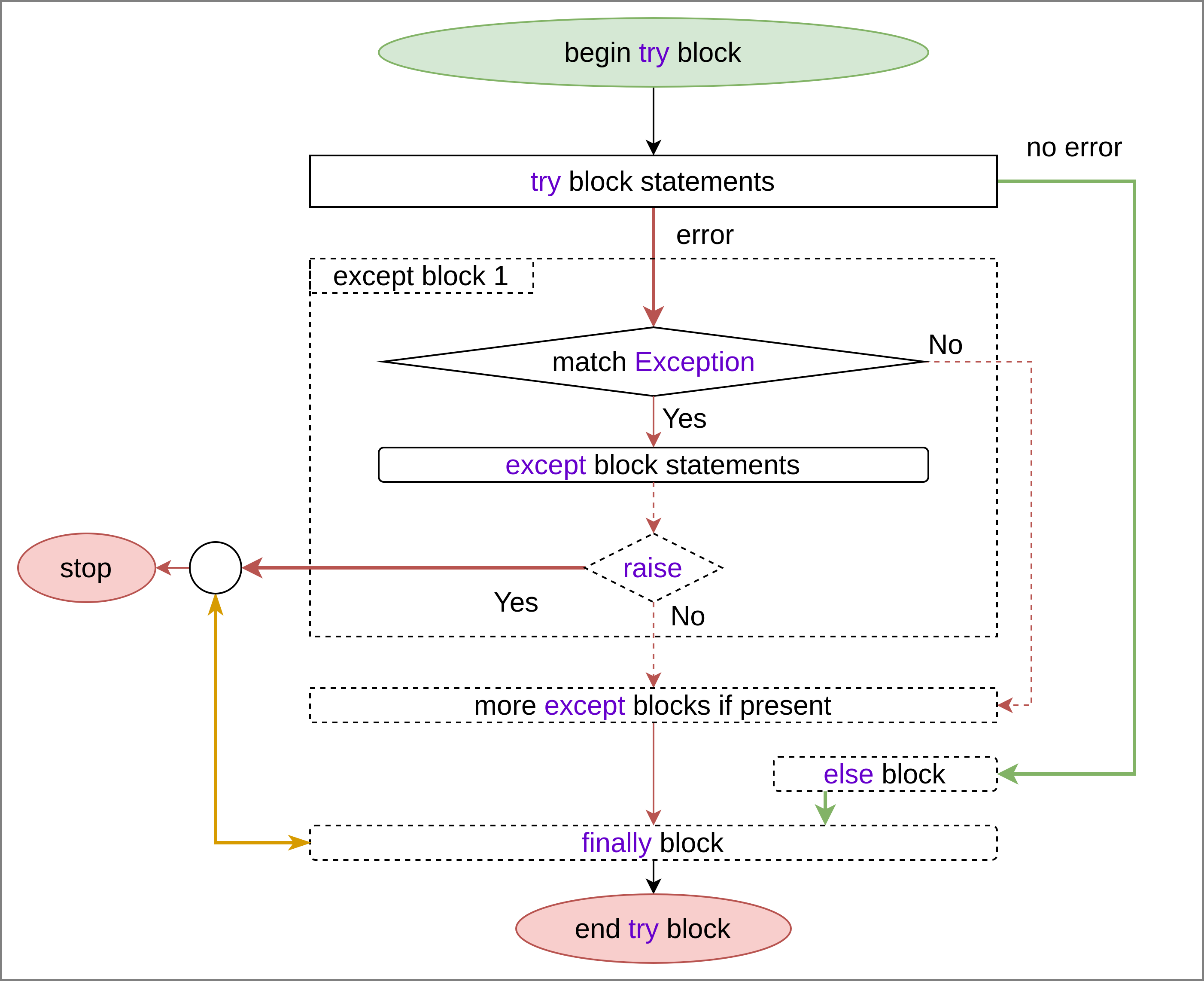

try...[except]...[else]...[finally]

try:

# try code block

[except Exception as e:

# except code block

[raise]]

[else:

# else code block]

[finally:

# finally code block]except or finally blockelse clause (if present) should be after the except blockexcept clausesraise statement and else block are optionaltry block statements are always evaluated firstexcept blocks are run when they trap specified error

raise statement is hit

finally block is run<Exception type> raisedelse block is run in case of no errorfinally block is run always, error or no error

except blocksexcept statement in a try block is used to declare an except block. They can be used in 2 forms.

except <Exception type>except <Exception type> as <variable name>except block is run if there is a run time error while executing try block and the error matches the <Exception type> specified.

When second form is used, <variable name> is bound to the <Exception type> object.

There are 2 concepts involved.

Exception is supposed to be handled, e.g. NameError, TypeError, etc.The first concept is of using the exception type. Base Exception catches all known errors and is the most generic. In the beginning it should be enough. As the requirements increase there is a need to specify more specific errors. For multiple except blocks, it is recommended to have specific exceptions before generic exceptions

The second is the error object. In the beginning it is not of much use as handling the exception should be enough, but as you progress it is this object which helps in dealing different errors differently as it holds a lot of information, like the traceback.

Try blocks are generally used to intercept expected errors and control the outcome if error occurs, use case depends on the context. e.g.

This is an example for nesting different control flow techniques.

The same problem serves as a use case for using recursive functions which is discussed in Section 13.9.1.3.

while True:

try:

some_int = int(input('Enter an integer...'))

print(some_int)

break

except ValueError:

continue