def some_func(): pass

def some_func(): ""13 Functions

13.1 Introduction

13.1.1 Terminology

Historically, as the programming languages were evolving, the terminology reflected the state at the time. The terminology has spilled over loosing its context. Below is what was the terminology with intended context.

- Sub-routine: any named block of code that can be called (run) using its name

- Procedure: any sub-routine that

- has side effects

- does not take any input

- does not return anything

- (Pure) Function: any sub-routine that

- does not have side effects, does not leave its trace after execution

- takes inputs and operates only on the inputs

- returns something

- Procedure: any sub-routine that

In current popular languages there are just functions which can take any of the forms, function is the only term in language specification.

13.1.2 Background

Functions are a major pillar in any programming language, that help to repeat related tasks with code reuse.

At more abstract level, functions provide

- means of combination

- build smaller pieces and then join to make a bigger piece

- means of encapsulation

- hide details of implementation during usage

- means of abstraction:

- create blueprints of functionality

A function can be thought of as a black-box which may takes some input and produces some output or performs a task in background. Black boxes can be combined to create new black boxes.

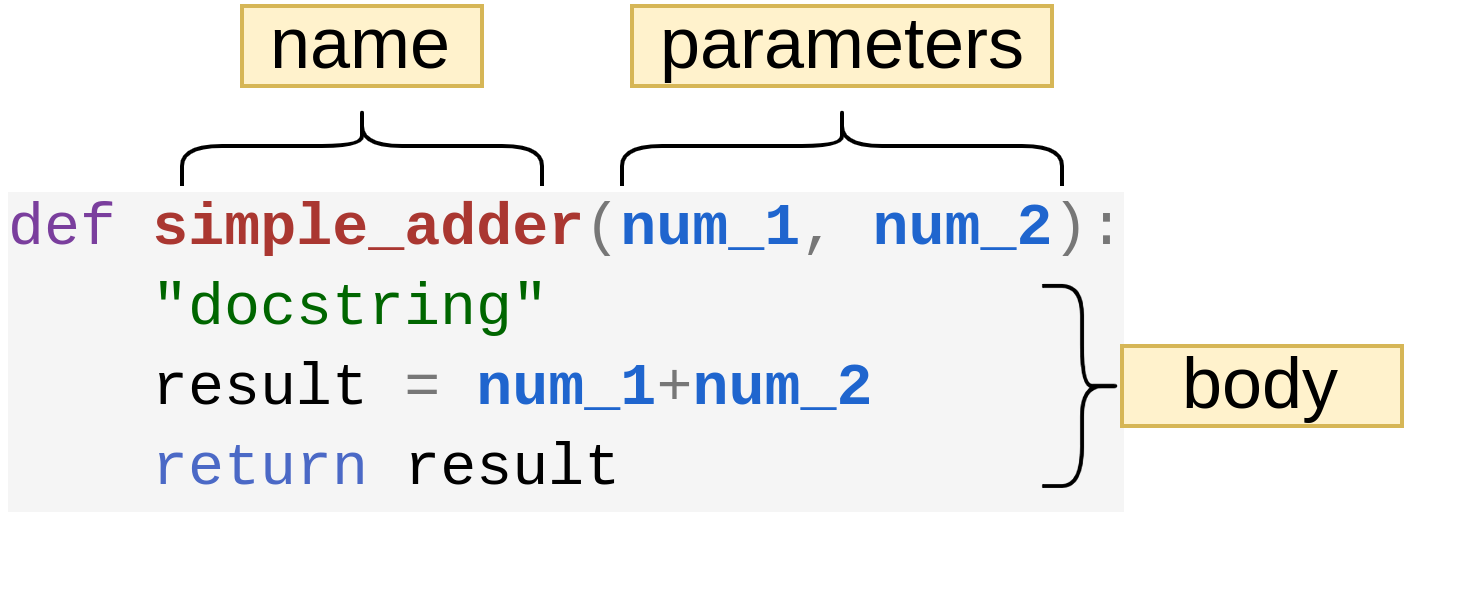

13.1.3 Components of a function

- A simple function has following parts

- name

- parameters (optional)

- body (code)

- docstring (optional, beginning)

- return statement (optional)

13.1.4 Usage

A function can be

- called

function_name(parameter_1 = argument_1, ...) - stored

variable_name = function_name - passed

function_name_2(variable_name = function_name)

Functions can be called from any block, e.g. control flow block, body of another function. This allows means of combination, to build smaller functionalities and then join them to create a bigger function or program.

13.1.5 Functions are callable

- In simplest form a function call

- (optionally) receives arguments (value) for some predefined parameters

- (optionally) runs some code to execute certain operation[s]

- (optionally) returns some object[s]

- e.g.

some_func(),len(iterable),add(1, 2), …

- A function call can have side effects

- it does something in background, e.g. write to a database

- may or may not return any object

13.1.6 Functions are objects

In Python, like many other high level programming languages, functions are objects, therefore they can be

- assigned to a variable

- stored in a data structure (such as

list,tuple,dictionary, …) - passed to a function as an argument

- returned from a function

13.1.7 Different forms of functions

- Regular functions

- Anonymous functions: lambda expressions

- Partials: new function from an existing function with partial set of arguments provided

- Higher order functions: take function[s] as arguments and optionally return function[s]

13.1.8 Lifetime of functions

This section might not be fully understood before going through namespaces and scopes (Chapter 16) in architecture part of the book, where this is covered in more detail.

- At compile time (when the function definition is read)

- function object is created without evaluation, except

- objects are created for parameters with default values

- default values are objects stored in function object

- code is stored in the function object

- variables are assigned scopes

- function object is created without evaluation, except

- At run time (when the function is called)

- a new local scope is created in the calling environment

- variable names are looked up in assigned scopes

- function code is evaluated

13.2 Basic Specifications

13.2.1 First line

- statement starting with keyword

defdeclares a function definition defmust be followed by- function name

- a pair of parenthesis ending in

:

- parenthesis on the first line can optionally contain parameters

- parameters can optionally be annotated with

type- types are not evaluated

- e.g.

def func(a:int, b:str) -> str:-> strindicates the function returns astrtype object

- detailed discussion on parameters separately in parameters section

- parameters can optionally be annotated with

- colon (

:) must be followed by function body- if function body is too short it can be included on the same line

def function_name(a, b):

# code block

return result_objectBelow are examples of some short functions that can be declared on a single line. Last 2 are also example of using functions as placeholders, functions which are declared but have to be implemented later.

def some_short_func(x, y): return x + y

def some_short_func(): pass

def some_short_func(): ""13.2.2 Function body

- must be indented

- first line can optionally be a doc string

- optionally contain return

- optionally contain pass

def function_name(a, b):

"""function description

parameter 1: description

returns: description

"""

# code block

return result_object13.2.3 Doc strings

Doc strings are used to document functions. They can be multiline strings.

Doc strings are critical for large projects or packages with a lot of code. Editor help pop ups use the doc strings.

sphinx is the most popular python framework for automating documentation.

Even for small projects documentation can be useful for later use. Comments can be used for documentation, but automated doc strings providers help structure the documentation and make the process efficient.

For example, VSCode extension, autoDocstring - Python Docstring Generator can be used to assist in creating docstrings.

Using such tools help use best practices evolved by experience of developers.

13.2.4 pass statement

passstatement does not alter control flow- used as place holder for functions to be implemented

- can be replaced by a doc string

13.2.5 return statement

- syntax:

return [expression_list] expression_listcan be- a single object

- comma separated objects which are turned to a tuple

- control flow:

- when a

returnstatement is hit anywhere in the code block- expression_list, if present, is evaluated and returned

Nonereturned if there is no expression- function call is exited

- exception: when

returnis hit fromtry..except..else..finallyblockfinallyblock is run before the function call is exited

- when a

13.3 Parameters and arguments

13.3.1 Definitions

Parameters: are input variables in context of defining the function

Arguments: are variables or objects passed to parameters in context of calling the function

Example

aandbare parameters ofsome_func10andxare arguments ofsome_func

def some_func(a, b):

# code block

pass

x = "a string"

some_func(10, x) # function call13.3.2 Object passing

In Python, the arguments are passed as object references to the parameters. Therefore if the object passed is mutable, changes will be propagated.

an_int = 10; a_string = "abc"; a_tuple = (an_int, a_string)

a_list = [*a_tuple]

def a_func(x1, x2, x3, x4):

x4.append("xyz")

print('-'*20)

print('from within function call')

print(x1 is an_int, x2 is a_string, x3 is a_tuple, x4 is a_list)

print('-'*20)

return x1, x2, x3, x4

ret_tuple = a_func(x1=an_int, x2=a_string, x3=a_tuple, x4=a_list)

print(ret_tuple[0] is an_int, ret_tuple[1] is a_string, \

ret_tuple[2] is a_tuple, ret_tuple[3] is a_list)

print(f'{a_list=}')>>> --------------------

>>> from within function call

>>> True True True True

>>> --------------------

>>> True True True True

>>> a_list=[10, 'abc', 'xyz']13.3.3 Argument types

Based on how parameters are defined arguments can be passed in different ways

positional arguments: are passed to parameters using position during a function call

keyword arguments: are passed to parameters using keyword (parameter name) during a function call, also called named parameters

optional/default arguments: any parameter with default value specified makes the argument optional

- with positional arguments order has to be kept in mind

13.3.3.1 Examples

def some_func(a, b):

passsome_func(10, 20) # passed as positional

some_func(a = 10, b = 20) # passed as keyworddef some_func(a, b=20): # b is optional

print(f'{a = }, {b = }')some_func(10)>>> a = 10, b = 20some_func(10, 30)>>> a = 10, b = 30some_func(a = 10)>>> a = 10, b = 20some_func(b = 30, a = 10)>>> a = 10, b = 3013.3.4 Specifications

- General structures for defining parameters (

/,*,**)function_name(<pos or kw>)function_name(<pos>, /, <po or kw>, *, <kw>)function_name(<pos>, /, <po or kw>, *args, <kw>, **kwargs)

- regular arguments: by default all arguments can be passed as positional or keyword subject to

- positional arguments must come before keyword arguments

- once a keyword argument is given all remaining arguments are keyword

- after one default argument, remaining must be default

- except for keyword only arguments

- separation

/is used to separate positional only arguments*is used to separate keyword arguments

- collection (variadic arguments)

*argscollects all available positional arguments as a tuple- has to be defined after other positional arguments if present

argsis just convention, can be name of choice, but recommended

**kwargscan collect all available keyword arguments as a dictionary- has to be defined at the end

kwargsis just convention, can be name of choice, but recommended

*and*argsmark the beginning of keyword arguments, hence cannot precede/

13.3.5 Use cases

- as a user of packages

- regular arguments are needed mostly

- while using external packages familiarity with the specifications will help

- positional only parameters are used when

- parameter names have no meaning

- reliance on keyword for passing arguments has to be avoided

- e.g.

printfunction: multiple objects can be passed before any kw arg

- keyword only parameters are used when

- names have special meaning

- reliance on positional arguments has to be avoided

- e.g.

printfunction:end,sepetc. have to be passed after all positional variadic args as kw

13.3.6 Examples

Regular arguments: by default all arguments can be passed as positional or keyword subject to

- positional arguments must come before keyword arguments

once a keyword argument is given all remaining arguments must be keyword

def some_func(a, b, c):

passsome_func(10, 20, 30)some_func(10, 20, c = 30)some_func(10, b = 20, c = 30)

some_func(a = 10, 20, 30)some_func(10, b = 20, 30)some_func(a = 10, b = 20, 30)

13.3.6.1 Separation

/is used to separate positional only arguments*is used to separate keyword arguments

def some_func(pos_1, pos_2, /, pos_or_kw_1, *, kw_1, kw_2):

print(f"{pos_1=}, {pos_2=}, {pos_or_kw_1=}, {kw_1=}, {kw_2=}")some_func(1, 2, 3, kw_1=4, kw_2=5)>>> pos_1=1, pos_2=2, pos_or_kw_1=3, kw_1=4, kw_2=5some_func(1, 2, pos_or_kw_1=3, kw_1=4, kw_2=5)>>> pos_1=1, pos_2=2, pos_or_kw_1=3, kw_1=4, kw_2=5some_func(1, pos_2=2, pos_or_kw_1=3, kw_1=4, kw_2=5)>>> Error: TypeError: some_func() got some positional-only arguments passed as keyword arguments: 'pos_2'13.3.6.2 Variadic arguments

- collection (variadic arguments)

*argscollects all available positional arguments as a tuple- has to be defined after other positional arguments if present

argsis just convention, can be name of choice, but recommended

**kwargscan collect all available keyword arguments as a dictionary- has to be defined at the end

kwargsis just convention, can be name of choice, but recommended

def some_func(*args, **kwargs):

print(f'{args}')

print(f'{kwargs}')some_func(1, 2, 3)>>> (1, 2, 3)

>>> {}some_func(1, 2, 3, a = 4, b = 5)>>> (1, 2, 3)

>>> {'a': 4, 'b': 5}argsis just convention, can be name of choice, but recommendedkwargsis just convention, can be name of choice, but recommended

def some_func(*args_tuple, **kw_dict):

print(f'{args_tuple}')

print(f'{kw_dict}')some_func(1, 2, 3)>>> (1, 2, 3)

>>> {}some_func(1, 2, 3, a = 4, b = 5)>>> (1, 2, 3)

>>> {'a': 4, 'b': 5}13.3.6.3 More Examples

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13.4 Examples

13.4.1 Check primes

Prime is a positive integer greater than 1 which is divisible only by 1 and itself. E.g. 2, 3, 5, …

Given a positive integer check if it is a prime. Print a message confirming the result.

def check_prime(num: int) -> None:

"""

check if a number is prime and print the result

num: positive integer

returns: None

"""

if not isinstance(num, int):

print(f'{num} is not an integer')

return

if num <= 1:

print(f'{num} is not a positive integer greater than 1')

return

divisors = []

for i in range(1, num + 1):

if num % i == 0: divisors.append(i)

if divisors == [1, num]:

print(f'{num} is a prime')

else:

print(f'{num} is not a prime')check_prime(10)>>> 10 is not a primecheck_prime(23)>>> 23 is a primecheck_prime(1)>>> 1 is not a positive integer greater than 1check_prime(-2)>>> -2 is not a positive integer greater than 113.4.2 GCD

Implement the gcd algorithm using a function that takes 2 numbers as input and returns the greatest common divisor.

Below is gcd algorithm to find the greatest common divisor of 2 integers.

- given 2 numbers a, b

- find remainder of a, b (modulo operator

%gives the remainder) - if remainder is zero then b is the gcd

- replace a with b and b with remainder (in python this is 1 step using multiple assignment)

- goto to step 1

- find remainder of a, b (modulo operator

Below is what was implemented using while loop in control flow chapter. Note that every time gcd has to be calculated inputs have to be changed and the whole code has to be run.

a, b = 9, 6

rem = a % b

while rem != 0:

print(f'{a = }, {b = }, {rem = }')

a, b = b, rem

rem = a % b

print(f'{a = }, {b = }, {rem = }')

print(b)>>> a = 9, b = 6, rem = 3

>>> a = 6, b = 3, rem = 0

>>> 3def calc_gcd(num_1: int, num_2: int) -> int:

"""

Calculate and return the greatest common divisor of 2 integers

"""

rem = num_1 % num_2

while rem != 0:

num_1, num_2 = num_2, rem

rem = num_1 % num_2

return num_2Having defined the function, it can be called multiple times with different values without worrying about the implementation. This serves as an example of means of encapsulation.

calc_gcd(3, 9)>>> 3calc_gcd(12, 45)>>> 313.5 Caveat for default values

When using mutable data types (like list, dictionary or set) as default values for function parameters, the behavior has to be looked out for. Default values are typically used for immutable data types like numbers, strings or bool.

It is important to note that default values are created once in memory, when the def statement is executed for creating the function object, i.e. at compile time. Not during a function call.

Check the result of below function calls. Trying out python tutor will help understand this more clearly.

def some_func(num, some_list=[]):

some_list.append(num)

return some_list

print(some_func(1))

print(some_func(2))>>> [1]

>>> [1, 2]Note that during second call same list was used. There are situations when this default behavior has to be avoided. Below is an approach to get around this.

def some_func(num, some_list=None):

if some_list == None: some_list = []

some_list.append(num)

return some_list

print(some_func(1))

print(some_func(2))>>> [1]

>>> [2]13.6 lambda expressions

Lambda expressions are anonymous and short functions, typically used to create very short functions to be passed around or for cleaner syntax.

Generic name is anonymous functions. Most languages provide a mechanism to create and pass anonymous functions. In Python, they are called lambda expressions.

Syntax

lambdakeyword is used to create lambda expressionslimited to a single expression

returnkeyword is not required, expression is returnedexample:

lambda x, y: x * y

f = lambda x, y: x * y

print(f)>>> <function <lambda> at 0x774be7176a70>print(f(2, 3))>>> 613.7 Partials

Partials are functions created from other functions by passing a subset of required arguments.

functools module in standard library provides a higher order function partial to create partials.

13.7.1 Use cases

Partials are often used in functional programming where functions are passed around as arguments. e.g. functionals like map, filter and reduce take functions as argument where partials are needed. They are discussed in Section 13.8.1.

Another use is when an existing function has to be used multiple times with certain set of arguments specified.

As an example in an application if print function is needed to be used multiple times with argument sep="\n" then a partial can be created using original print function.

import functools as ft

custom_print = ft.partial(print, sep="\n")

some_list = [1, 2, 3]

custom_print(*some_list)>>> 1

>>> 2

>>> 313.8 Higher order functions

Higher order functions evolved as part of functional programming paradigm where functions are treated as objects.

Higher order functions are functions that

- take function[s] as input

- optionally return function[s]

Higher order functions along with rules of scoping are used to create different types of functions

Design patterns created using higher order functions

- Map-Reduce: apply some function to elements of a collection

- Factory functions: create new functions based on some input argument

- Decorator functions: add some standard functionality to a function

Python standard library has some modules/packages to help with these

13.8.1 Map Reduce

Map-Reduce is a design pattern to work with collections. These are newer features in high level languages like Python. They provide a better and cleaner alternative to iterative solutions using loops for working with collections.

Filter is a special case of map. Collectively these are also referred to as functionals.

Functionals are a good example of design patterns to improve desired properties of program. All the 3 forms improve code readability as the syntax is concise and it is easier to spot what is being done by isolating it from iteration.

For example, map is a generic concept which improves

- Readability

- iteration is isolated from what operation is being done, hence better readability

- Modularity

- map is responsible for iteration

- function passed is responsible for operation to be applied to each element

- Extensibility

- function passed can be anything, so different operations can be applied by defining new functions without impacting the core functionality of iterating and applying the function.

- Testability

- it is easier to test and debug as the structure is modular

- Efficiency

- map is faster than loop but slower than comprehensions

13.8.1.1 Map

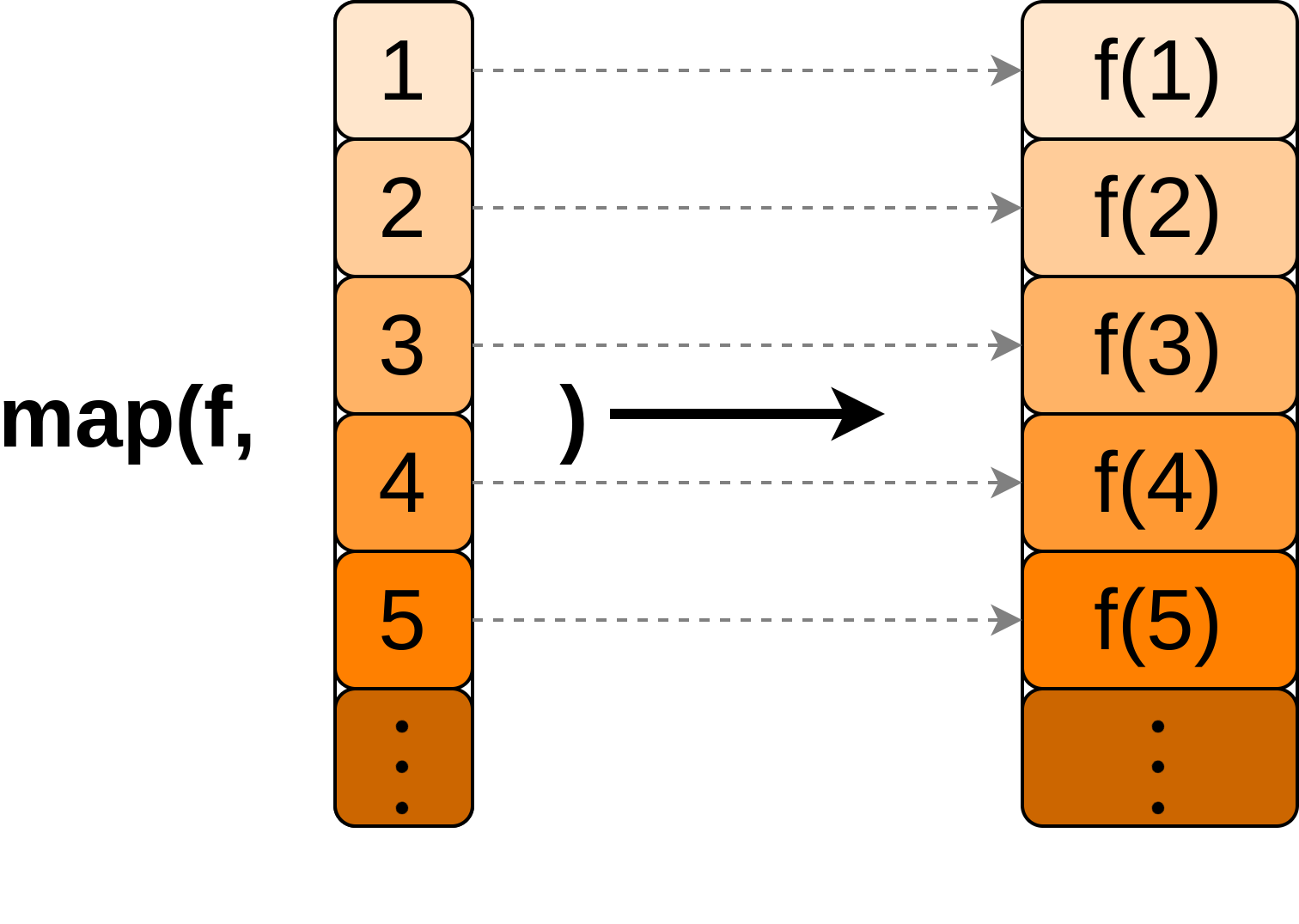

Map is a generic concept of applying (mapping) a function to all elements of a collection or multiple collections in parallel.

Map is a better alternative to for loops as code readability is improved as what is being done is isolated from iteration.

Syntax

map(function, iterable[, iterables])is the Python implementation- returns an iterator (consumable, can be used once)

With single iterable: function applied should take 1 argument which will be elements of the iterable

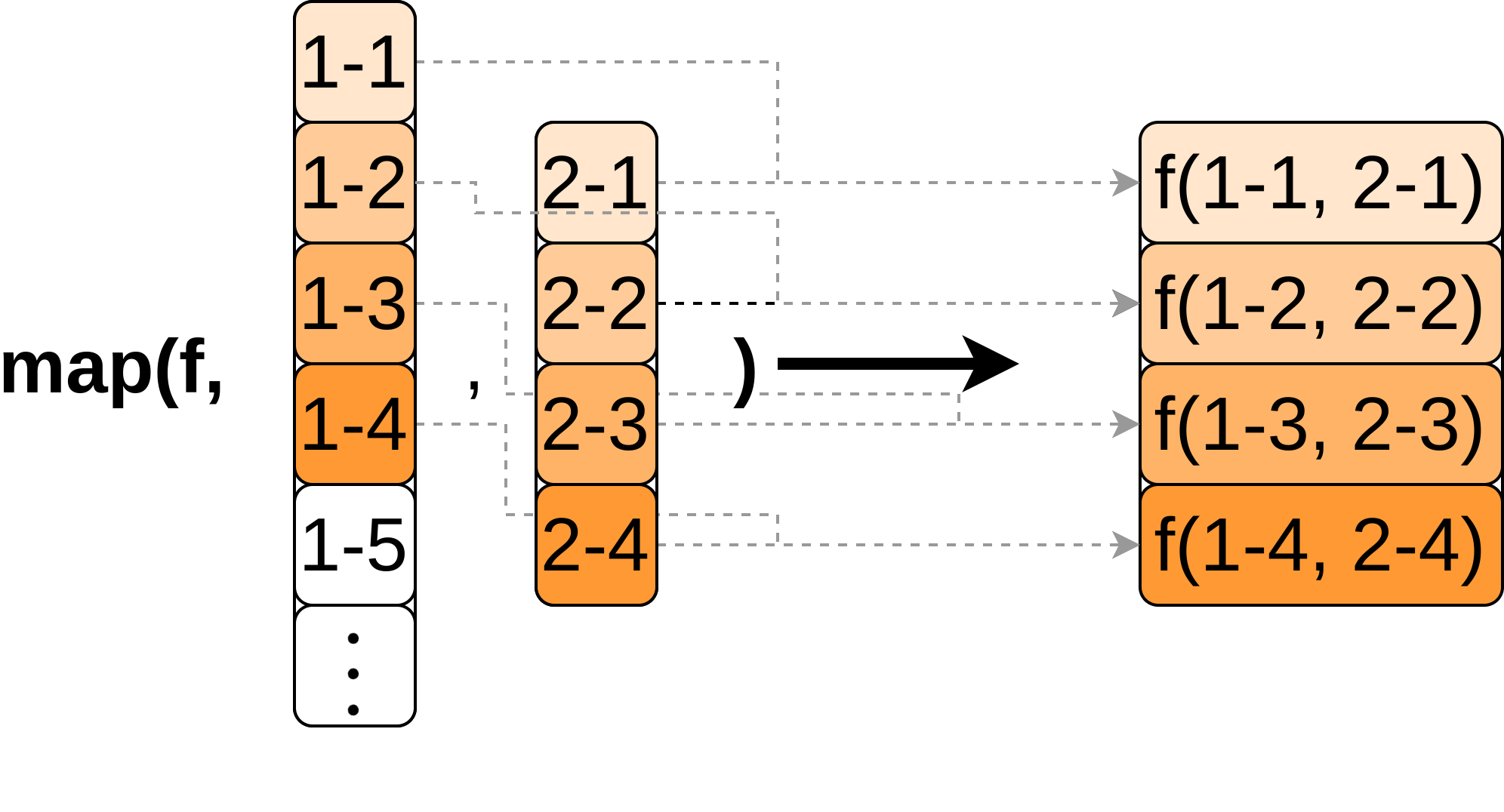

With multiple iterables

- function applied should take as many arguments as iterables

mapstops at iterable of shortest length, if lengths are different

13.8.1.1.1 Example: Single iterable

To find the square of all numbers in a list (container) below are different solutions. Note that underlying operation is simple, apply some operation to elements of a collection. This is a very common situation encountered while programming.

some_list = list(range(5))13.8.1.1.1.1 Loop

sqrd_list = []

for x in some_list:

sqrd_list.append(x**2)>>> sqrd_list = [0, 1, 4, 9, 16]13.8.1.1.1.2 Map

def sqr(x):

return x**2

sqrd_itr = map(sqr, some_list)>>> list(sqrd_itr) = [0, 1, 4, 9, 16]13.8.1.1.1.3 Map & lambda

sqrd_itr = map(lambda x: x**2, some_list)>>> list(sqrd_itr) = [0, 1, 4, 9, 16]13.8.1.1.2 Example: Multiple iterables

- add numbers in 2 tuples

Note that lengths of iterables is different in example so result is accordingly of length of shortest iterable.

If function to map is complex, define a regular function and pass the name to map.

tuple_1 = 1, 2, 3

tuple_2 = 4, 5tuple(map(lambda x, y: x + y, tuple_1, tuple_2))>>> (5, 7)tuple(map(lambda x, y: x + y, tuple_2, tuple_1))>>> (5, 7)13.8.1.2 Filter

Filter is a generic concept of filtering values from a collection using certain conditions. Note that it is a special case of map.

Syntax

filter(function, iterable)is provided in Python- returns an iterator (consumable, can be used only once)

- function should return true or false when acting on an element

- if function is

Nonethen all truthy elements are returned

13.8.1.2.1 Example: None

some_list = [1, 0, None, '', 'abc', tuple()]list(filter(None, some_list))>>> [1, 'abc']Below is the same task done using iterative solution.

filtered_list = []

for item in some_list:

if item: filtered_list.append(item)

filtered_list>>> [1, 'abc']13.8.1.2.2 Example

- filter positive integers from a list

some_list = [-2, -1, 0, 1, 2][*filter(lambda x: x > 0, some_list)]>>> [1, 2]Below is the same task implemented using iterative solution.

filtered_list = []

for item in some_list:

if item > 0: filtered_list.append(item)filtered_list>>> [1, 2]13.8.1.3 Reduce

Reduce is a generic concept of aggregating elements of a collection into single result.

The actual underlying operation is to apply a function (operation) to 2 items at a time recursively.

Let a collection of n elements be \(collection = [e_0, e_1, e_2, e_3, e_4, \cdots, e_{n - 1}]\). What reduce does is

- result of step 1: \(r_1 = f(e_0, e_1)\)

- result of step 2: \(r_2 = f(r_1, e_2)\)

- result of step 3: \(r_3 = f(r_2, e_3)\)

- …

- result of step n - 1: \(r_{n - 1} = f(r_{n - 2}, e_{n - 1})\)

Optionally an initial value can be given which is used as the base case, step 1 uses this value and the first element. This is also used in case the collection has 0 or 1 element.

Note that there will be an error if the collection is empty and no initializer is specified.

For example, sum of some numbers is applying reduce and cumulative sum of some numbers is the intermediate result of reduce.

Reduce is less often used in comparison to map and filter most often used to create aggregate tables and data.

Python standard library has tools to apply reduce and accumulate.

functools.reduce(function, iterable[, initializer])itertools.accumulate(iterable[, func, *, initial=None])

13.8.1.3.1 Example

To find the sum of numbers in a list using iterative solution and reduce.

some_list = list(range(10))

print(some_list)>>> [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]sum_itr = 0

for num in some_list:

sum_itr += numsum_itr>>> 45import functools as ft

import operator as op

sum_red = ft.reduce(op.add, some_list, 0)sum_red>>> 45Instead of defining

add_func = lambda x, y: x + y,operatormodule was used.

13.9 Recursive functions

- Recursion is a generic concept of repeating a smaller well define task to get to a solution using base case[s]

- e.g. gcd algorithm

- Recursion can be implemented using iterative solution or recursive functions

- recursive functions are not most efficient but better in terms of

- code readability

- maintainability

- recursive functions are not most efficient but better in terms of

- Recursive functions call themselves from within themselves to terminate when the base case[s] is reached

- base case[s] need to be defined carefully to avoid infinite recursive calls

- Do not use recursive functions unless it is unavoidable

- merge sort is an example of recursive algorithm that is efficient

To understand how recursive functions create nested scopes, Python tutor is a good tool. It helps visualize how nested local scopes are created and destroyed at run time during recursive function calls.

Recursive functions are used in algorithms, specially when normal approaches like iteration become infeasible. Therefore in the beginning there is not much point to spend a lot of time on this, but it is good to understand the concept as it might come handy in some situations. An example would be when there is an expected error that you want to handle and retry.

13.9.1 Examples

13.9.1.1 Factorial

\[ \begin{aligned} n! &= n*(n-1)*(n-2)*\cdots*1 \\ &= n * (n-1)! \\ 0! &= 1 \end{aligned} \]

def fact_iter(n):

result = 1

for i in range(1, n+1):

result *= i

return result

def fact_rec(n):

if n == 0:

return 1

else:

return n*fact_rec(n-1)13.9.1.1.1 Iterative Solution

13.9.1.1.2 Recursive solution

Note that recursive solution can be cleaned further using the ternary operator and lambda expression.

fact_rec = lambda n: 1 if n == 0 else n*fact_rec(n-1)13.9.1.2 GCD Algorithm

a, b = 9, 6

rem = a % b

while rem != 0:

print(f'{a=}, {b=}, {rem=}')

a, b = b, rem

rem = a % b

print(f'{a=}, {b=}, {rem=}')

print(b)Given 2 numbers a, b

- find remainder of a, b (modulo operator

%gives the remainder) - if remainder is zero then b is the gcd

- replace a with b and b with remainder (in Python this is 1 step)

- goto to step 1

- find remainder of a, b (modulo operator

Earlier this was solved using

whileImplement this using

- regular function

- recursive function

>>> a=9, b=6, rem=3

>>> a=6, b=3, rem=0

>>> 313.9.1.2.1 Regular function

def find_gcd(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"""

find the greatest common divisor of 2 integers a and b

"""

rem = a % b

while rem != 0:

a, b = b, rem

rem = a % b

return bfind_gcd(35, 28)>>> 713.9.1.2.2 Recursive function

def find_gcd_rec(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"""

find greatest common divisor of 2 integers a and b using recursion

"""

rem = a % b

if rem == 0:

result = b

else:

result = find_gcd_rec(b, rem)

return resultfind_gcd_rec(35, 28)>>> 7Note that above code can be further cleaned as below by simply reorganizing the placement of return statement as only one option is to returned and a function ends if it hits the return statement.

def find_gcd_rec(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"""

find greatest common divisor of 2 integers a and b using recursion

"""

rem = a % b

if rem == 0:

return b

else:

return find_gcd_rec(b, rem)This can be further cleaned by using ternary operator, X if condition else Y.

def find_gcd_rec(a: int, b: int) -> int:

"""

find greatest common divisor of 2 integers a and b using recursion

"""

rem = a % b

return b if rem == 0 else find_gcd_rec(b, rem)13.9.1.3 Handling exceptions

In the control flow section, the example, Section 12.4.2.3.1, was to ask user input until it is correct. The solution was implemented using while and try blocks.

The same thing can be achieved using a recursive function with max number of tries allowed.

def get_an_integer(max_count=5, count=1):

"""

Ask user to input an integer until integer is provided

or maximum number of trials expire

"""

try:

some_int = int(input('Enter an integer...'))

return some_int

except ValueError:

print(f'This was try number {count}, and was not an integer.')

if count < max_count:

count += 1

get_an_integer(count=count)

else:

print(f"maximum tries ({max_count}) reached")